A Conversation with Dafina Ward of the Southern AIDS Coalition

FCAA recently sat down with Dafina Ward, Executive Director of the Southern AIDS Coalition (SAC), to talk about the organization and its work as an intermediary funder.

Intermediary funding is a topic that comes up frequently for FCAA members. One of the recommendations within the Converging Epidemics report was increased and longer-term support to intermediary funders that are closer to—and oftentimes part of—grassroots community advocacy and actions. Our conversation with Dafina helps set the stage for additional research and dialogue around intermediary funders that FCAA will be facilitating later this year.

But first, let us introduce you to Dafina, who joined the SAC in 2018 to manage its grantmaking through the Gilead COMPASS Initiative—a decade-long, $100-million commitment to address HIV/AIDS in the southern United States. As a Gilead COMPASS Initiative Coordinating Center, SAC provides a range of grants and capacity-building services to organizations and leaders in the twelve southern states.[1] Here is what she had to tell us about SAC:

Can you tell us about the history of the Southern AIDS Coalition?

The Southern AIDS Coalition (SAC) was founded 20 years ago by a group of dedicated southerners who were on the frontlines of addressing HIV in the region—leaders of community-based organizations, policy advocates, and public health officials—all of whom recognized that the South was not receiving an equitable share of federal resources in alignment with HIV cases in the region. SAC educated the community and engaged new leaders and advocates in the fight. They had a big impact.

SAC was born out of fighting for the South, and that’s what we continue to do today. We’re still focused on policy and advocacy, and we have added a number of other portfolios, including grantmaking, community-based organizations, leadership development, training and capacity-building, as well as health department engagement focused around EHE (Ending the HIV Epidemic)jurisdictions and providing technical assistance in the areas of community engagement and strategy for systems coordination.

It’s also important to mention that SAC is proud to represent communities most impacted by HIV in terms of our staff. I’m the first Black woman to lead the organization. Our staff and partners represent Black, Brown, and rural communities, those who are living with HIV or have had very personal experiences with it. We really want to model what the goal should be around inclusion and leadership development. That means providing opportunities to people from the communities that are closest to HIV and to the disparities that we’re working against.

The SAC is a coordinating center of Gilead’s COMPASS Initiative—can you tell us a little about that strategic grantmaking?

We’ve been a Gilead COMPASS Initiative Coordinating Center since 2018, and this was truly our first foray into grantmaking as an organization. SAC is one of four coordinating centers and the only one that’s a community-based organization.

COMPASS uses a collective impact model: the four coordinating centers work very closely to build strategies around grantmaking, training, capacity-building, and shared learning with organizations across 12 Southern states. We do one large collective grantmaking opportunity every 18 months — offering grants of about $100,000 each — in our four respective focus areas of expertise. SAC is focused on HIV stigma reduction.

Each coordinating center also has its own formative grant process; ours is the SPARK grant, which offers funding for communities to create innovative messaging around reducing HIV stigma, especially in rural areas. In 2020, we expanded the SPARK grant to also fund programs that address social isolation—recognizing the correlation often between stigma and loneliness, which was only magnified during the pandemic.

Have SAC’s existing relationships in the South been beneficial in your funding work?

Being part of this initiative and a funder has been really amazing, because the community already trusts us. We have relationships we’ve built over the last 20 years. When dealing with traditional funders, grantees can feel hesitant to share what’s not working because there’s always the threat of losing their resources. When you’re an intermediary funder that is also a grantee, you just have a different perspective around how you engage with folks. You want to bring the anxiety down. You want grantees to know that they are supported, which comes down to nurturing the relationship and providing support in the areas where they need it most.

I asked one grantee, “What in your heart brings you to do this work every day?” His first response was, “I’ve never had a funder talk to me like this. Funders never ask me that.” He explained that he felt he was able to make a positive impact and he wanted to do that. And those are the kinds of beautiful relationships that you build as an intermediary funder. We have really enjoyed working in this capacity.

How do you engage grantees in terms of funding decisions and priorities?

We are very proud of our work on that. We use a community participatory model for all of our review processes, and, historically, at least half of our reviewers are themselves living with HIV. We also ensure our reviewers represent a broad range of the communities that are most impacted. That means engaging people of trans experience, the LGBTQ+ community, rural communities, and the Latinx community. Making sure we have all of those voices at the table is really important.

With COMPASS, the community is also engaged in the development of the RFPs (request for proposals). We encourage people to review the proposals and weigh in to ensure we’re creating RFPs that are low barrier.

During our 3rd Annual Southern HIV/AIDS Awareness Day this year (August 20, 2021), we are leading a movement that demonstrates how funding supports our efforts. We’re encouraging our partners to support, act and change our communities in the South. We especially want to amplify the work being done in the South to build a bridge of information, resources and support for people living with HIV/AIDS throughout the country.

How has this work, and the communities you serve, been impacted by COVID-19? What lessons has the SAC learned from COVID-19 that it will be taking forward?

We were already a remote organization, so we were really fortunate that we had that infrastructure. We realized we could provide capacity-building for grantee partners that were not accustomed to remote work, so we led sessions where we talked about things like remote management practices and self-care. Last summer, we even co-hosted virtual “break room“ spaces for our grantees with our partners in the Gilead COMPASS Initiative®. On a weekly basis these sessions became a place to unwind, enjoy a live DJ, and receive peer support from organizations who were working tirelessly during the pandemic.

We also listened to our grantees and gave them a lot of flexibility. We allowed grants to be transferred to general operations, rather than requiring the programmatic deliverables that were in place upon funding. As a result of COVID, we also created something we call “Spark Connections.” This allowed us to fund organizations to create things like virtual yoga classes for clients living with HIV, virtual support groups, and the capacity to get online or get Zoom accounts. We wanted people to have the ability to stay engaged because we recognized that isolation from COVID was doing a lot of harm. Going forward, SAC will continue funding work around connectivity. That’s one of the reasons we think intermediaries are so important, because we have that level of relationship where people can tell us, “Our clients and staff are really struggling. Here’s how you can help us.”

In addition, we recognize that those living with HIV/AIDS are currently living in an epidemic inside a pandemic. We must fight harder to end the HIV epidemic and end the COVID-19 pandemic. As we work to prevent new transmissions and build a better South for people living with HIV/AIDS, the rest of the country benefits from our success. As funders, it is also an opportune to learn from community-led efforts. This is a time for listening and supporting grassroots efforts to be responsive to community needs.

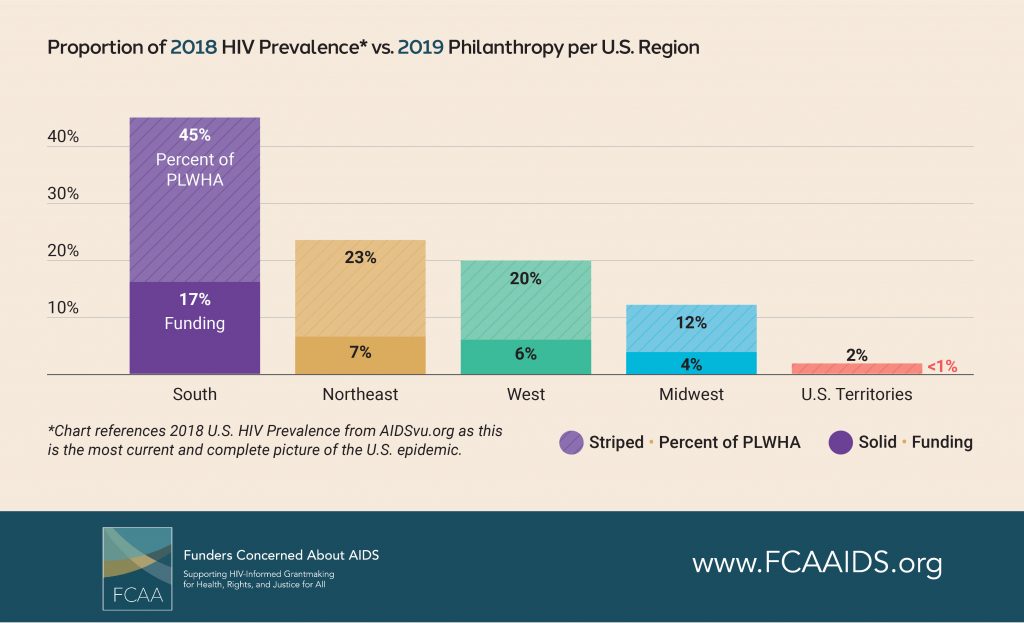

Our most recent resource tracking report highlighted that, while 45% of PLWHA in the U.S. reside in the South, the region only receives 17% of HIV-related philanthropic funding. If you could ask funders to help fill that gap, what would you ask for?

General operating support is always going to be number one. Folks need the overhead to run their organizations—and we (like many funders) were responsive to that need in light of the pandemic. Additionally, how do we build funding that centers organizational infrastructure? The pandemic has revealed that programmatic focus may have to shift in an instant. How do we ensure that organizations have the capacity to meet the greatest need—whatever might arise. There’s also a need to fund more advocacy work that is happening here in the region. Oftentimes, funders will put out a request for proposals related to the South, but they will still choose organizations that are not Southern-based—they just happen to do work in the South. Where the organization is based matters because that funding feeds back into the local community. I would really encourage funders to please fund in the South.

We also need to build networks and support movement-building from a policy as well service-delivery lens. For example, developing meaningful opportunities for networking and shared learning. There’s so much great work happening in pockets in the South. I wish there were money for dissemination so we could build models in different communities and see what works where. Those types of things would be really transformational for the region.

Funders also need to recognize that, in the South, we’re dealing with multiple systems of oppression and injustice; we can’t just talk about HIV without talking about housing discrimination, lack of Medicaid expansion, and the fact that many communities lack comprehensive sexual health education or protections for LGBTQ+ people. These are important disparities, that run deeper than HIV and also contribute to the regional disparities. There are so many challenges in the South that impact rates of HIV in our communities. Those things need funding. Funders should allow organizations and communities to define more broadly what the work to end HIV looks like. Trust that the community knows what it needs.

In FCAA’s latest strategic plan we highlight the importance of “HIV-informed grantmaking” in addressing the deeply ingrained injustices that underpin the epidemic. What does HIV-informed grantmaking mean to you?

It means acknowledging that everything that we’ve learned around HIV grantmaking is transferable to a range of needs and challenges outside of HIV. Funders who are not HIV-specific are likely very concerned about health disparities, about environmental justice, about affordable housing—and all of those things intersect with HIV.

When I talk about HIV in the South, I usually start with a map that the NAACP released in the early 1900s that shows states with the greatest rates of lynching. Of course, the South is where you have the greatest rates of lynching. Then I continue to layer other maps on top—maps reflecting which states have failed to enact anti-discrimination laws, where Medicaid has not been expanded, where there are limited to no protections for renters, where service deserts exist. As you layer those maps, the South continues to be highlighted. Funders who may not be HIV-specific should recognize that any funding affecting the South, or improving health outcomes in the South, is going to improve health outcomes around HIV. In fact, without addressing those other disparities—like affordable housing or environmental justice—we will not be able to significantly improve health outcomes around HIV.

We couldn’t have said it better. Thank you, Dafina, for sharing your experience. We can’t wait to hear what SAC does next!

[1] Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas