Cultivating Community in Cuyahoga County

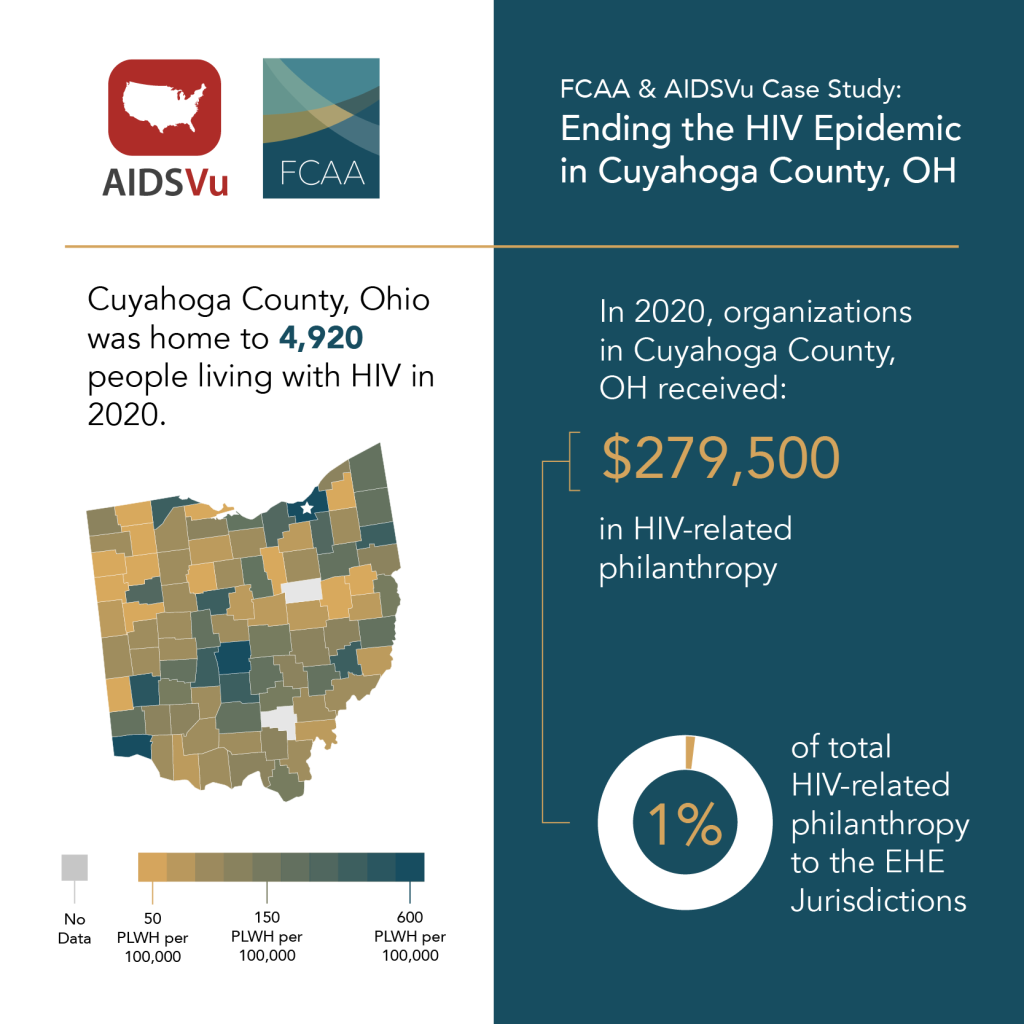

Cuyahoga County — with 4,920 people living with HIV in 2020 — is in one of 57 priority jurisdictions directly funded by the U.S Department of Health and Human Services under the Federal Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. Initiative (EHE).

When the County was devising its own specific Ending the HIV Epidemic plan in late 2019, community engagement was paramount. The Board of Health made the open call to various sectors — scheduling listening sessions and quarterly community advisory board meetings. Then a pandemic struck, and planning paused. The community was there and mobilized during the COVID response, and thanks to virtual options, EHE community feedback soon resumed.

“At that time, the only game in town was the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP). They (the community) knew the limitations of the program, and they were able to tell us, ‘These are the things that we are looking for, and we have heard that there are issues or barriers for individuals trying to access care,'” said Zachary Levar, of the Cuyahoga Board of Health. “The whole plan ended up being community driven.”

More recently, each quarter focused on a specific pillar of the EHE plan, utilizing a learn-share-build model for the meetings. This time around, the group brought a rich combination of committed advocates with histories in ACT UP Cleveland and North Coast HIV/AIDS Coalition membership teamed with U=U messaging.

Ending the HIV epidemic will require taking a broader approach than the four pillars found in the public health-oriented EHE Initiative, Julie Patterson, Director of the AIDS Funding Collaborative (AFC), said. This includes focusing on combating stigma and addressing HIV criminalization. Editor’s Note: Read the FCAA Member Spotlight feature on Julie Patterson from August 2021, here.

Since 1994, the AFC has mobilized nearly $13 million in funding for the HIV response in Greater Cleveland and was a key player in developing the county’s EHE plan. “We certainly have a powerful coalition. It’s set up so that people with HIV have, in many ways, the strongest voices.” Patterson added.

Whereas philanthropy can be nimble, Levar understands government funding comes with additional restrictions and reporting requirements. He implores local foundations to get involved with EHE. This can include, among other things, attending community engagement meetings, learning about their local HIV landscape, and seeing where they can fit in.

And there is room for more funders in this effort. Despite having a rate of HIV almost two times that of the entire state, according to data from Funders Concerned About AIDS, just $279,500 in HIV-related philanthropy was disbursed to organizations in Cuyahoga County in 2020, despite the fact that the county’s rate of HIV is twice the state of Ohio.

“This is a very large puzzle that EHE has brought to us. There are a lot of different people getting funding to do a lot of different work, but that doesn’t mean it’s all covered. I know that we’ve worked with the AIDS Funding Collaborative to achieve some of that, but we’re always open to getting more people involved in these programs. If they want to support any of them, we’re happy to make that happen,” Levar said.

In Patterson’s role at AFC, she mobilizes organizations of various sizes and provides coordination, technical assistance, and capacity building in addition to funding.

“The leading edge of HIV philanthropy is moving a lot in that trust-based philanthropy space and, within the U.S., that is more focused on racial equity. Locally, funders are investing in organizations that haven’t had the same opportunities to have funding before. This turns on its head some of the public health kind of training that we’ve always had, which was very outcomes focused,” she said.

Patterson is taking a cue from Harold Phillips, Director of the Office of National AIDS Policy (ONAP), when he said, “We want to do something bold. We want you to fund new organizations. We’re looking for disruptive innovation.

“It’s refreshing but challenging,” Patterson explained. “We’re always doing that dance between what can we do that is going to bring in new partners and people from communities who are most impacted, like key populations, and really partner with them in ways that will build their capacity and enable them to become stronger, yet at the same time, satisfy the folks who want to see outcomes.”

Funders from various sectors can contribute because the work of HIV prevention goes above and beyond HIV, Patterson added.

“Philanthropy really complements all the work we do in a major way,” Levar said. “With EHE, we [Cuyahoga County Board of Health] dedicated some money to smaller mini-grants that were geared towards these types of organizations, and we ended up contracting with a lot of the ones that came through this pipeline from AIDS Funding Collaborative. It was a testament to the fact that it actually was working, so that’s a big thing here.”

Patterson gives high praise to Celeste Watkins Hayes, PhD sociologist. Her book Remaking A Life: How Women Living with HIV/AIDS Confront Inequality describes the ideal HIV safety net and the ways that it can be a model for other systems and movements.

“It’s absolutely true. Our job at the AFC is to strengthen that overall safety net, and it includes everything across prevention and care, but it also includes all the innovation generated by people who are living with HIV, the support groups, and the coalitions and the opportunity,” Patterson said.

“I think that is our job,” she added. “If I can impress that upon people: philanthropy needs to support, but then sit back and let people do the work.”

Both Levar and Patterson are optimistic about EHE’s intentions in terms of community participation, innovative programming, and additional funding.

“We’re really well-positioned to accomplish the goals of EHE locally, and being a public health issue; that’s right in our wheelhouse,” Levar said. “I think that we’re the ones that are charged to take it and run with it here in Cleveland.”