MASEN DAVIS – SUSTAINABLE FINANCING FOR KEY POPULATIONS, 52ND UNAIDS PCB

The 52nd UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board (PCB) thematic segment topic was “Priority and key populations especially transgender people, and the path to the 2025 targets: Reducing health inequities through tailored and systemic responses,” and took place on 28 June 2023. Below you can read the full intervention delivered by Masen Davis during the panel discussion 3: Sustainable financing for key populations and community-led responses. Find the full agenda online.

Good afternoon. My name is Masen Davis, and I serve as the Executive Director of Funders Concerned About AIDS (FCAA).

FCAA is a global philanthropy-serving organization formed in 1987 to mobilize the resources needed to end the global HIV pandemic, and to build the social, political, and economic commitments necessary to attain health and human rights for all. Collectively, our members represent more than half of HIV-related philanthropy worldwide.

Are we on track?

Seven years ago, the global community made a commitment to end AIDS by 2030. As part of that strategy, many in this room recognized the pivotal role of key populations that continue to bear the brunt of this epidemic, including gay and bisexual men, sex workers, people who inject drugs, and transgender people – all who are still too-often marginalized, stigmatized, and criminalized.

Yet, as we’ve heard this week, funding for the global HIV response is alarmingly off track. This is true for donor governmental funding as well as non-governmental grantmaking alike.

Part of FCAA’s remit is to document philanthropic grantmaking related to HIV and AIDS worldwide. In recent years, we’ve seen a worrying trend of philanthropic institutions gradually withdrawing from HIV grantmaking; governments reducing their HIV funding allocations to institutions like UNAIDS and the Global Fund; and reauthorization of programs like PEPFAR becoming more politicized.

So, while I’ll focus most of my comments on sustainable financing for key populations, let me be very clear: It’s urgent that our governments and institutions recommit to fully financing the global HIV response. Any weakening of the HIV infrastructure will have far-reaching repercussions. It risks compromising entire healthcare systems, diminishing our capacity to respond efficiently and effectively to emergent crises, as exemplified by COVID-19 and the MPOX outbreak; and weakening civil society’s ability to respond to the needs of key populations.

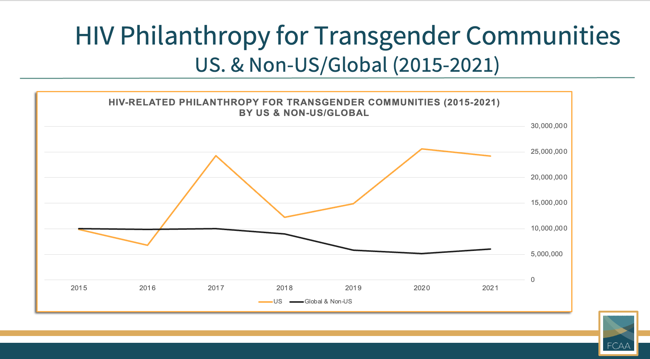

In 2021, FCAA found that HIV-related philanthropy totaled $692 million worldwide, representing 2% of total resources for HIV in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. 16% of these funds ($110.2 million) were dedicated to key population groups and 4% ($30 million) were directed to transgender populations. While philanthropic funding may seem quite low compared to donor and domestic government spending, these are quite significant because they are often more accessible to key populations; in fact, philanthropy represented 40% of worldwide grantmaking to trans populations between 2016 and 2018.

The relatively low levels of HIV funding for key populations, including transgender people, are especially concerning given the disproportionate impact of HIV on these groups.

Even though key populations and their sexual partners comprise less than 5% of the global population, they account for 70% of HIV infections globally and more than 90% of new HIV infections outside of sub-Saharan Africa. And transgender people are 12 times more likely to acquire HIV than the general adult population globally.

Also concerning is the inequitable geographic distribution of funding for trans populations. In 2021, 80% of funding for trans communities was directed to the United States, leaving only 20% to be distributed among the rest of the world.

This uneven allocation is unhealthy and unjust. Transgender people, like other key populations, are not unique to the US or to western nations. Transgender people exist in every country and culture – from Belgium to Brazil; from India to Iran; from Uganda to Uruguay. To acknowledge the existence of trans people is not meant to be a political statement, but simply a fact; indeed, to deny otherwise would unnecessarily politicize the issue.

Politicization threatens progress

I want to take a moment to speak to some political challenges threatening the HIV response and trans communities.

We have heard several speakers mention the “anti-gender” movement, a socio-political trend that commonly argues for a binary understanding of gender, rooted in biological sex, and opposes the official recognition of different expressions of gender identity (including transgender people). This movement has its roots in fundamentalist socio-political ideologies and is far-reaching. While the movement is largely linked to institutions and funders in the US and Europe, it has gained traction in various parts of the world and is contributing to the politization of transgender issues and, increasingly, HIV funding.

The financial resources fueling this anti-gender movement far exceed those available to impacted population groups. Our colleagues at the Global Philanthropy Project found that between 2013 and 2017, the anti-gender movement’s funding exceeded funds received by global LGBTI movements by more than 200% — and their funding tends to be long-term with few reporting requirements, allowing maximum flexibility and impact for anti-gender actors. As a result, if you read news articles or see policies challenging the inclusion of trans people in your countries, there’s a good likelihood that those were inspired and often even funded by anti-gender actors.

I don’t share all of this to be provocative. In our shared commitment to end the AIDS epidemic, understanding the nuances of anti-gender movements and their impact on vulnerable communities becomes essential. While it’s important to foster dialogues respecting diverse perspectives, it’s equally crucial to recognize that the anti-gender movement can perpetuate stigma, stereotypes, and discrimination. This is particularly relevant when discussing HIV and transgender issues. Transgender individuals often face significant barriers to accessing healthcare, including HIV prevention, testing, and treatment services. The anti-gender movement can exacerbate these challenges by promoting attitudes and policies that further marginalize and criminalize transgender people.

Putting a Face on these Issues

You’ve heard a lot about how violence, stigma, and discrimination; inequitable access to resources; lack of data collection; and healthcare and economic barriers all contribute to systemic obstacles to HIV prevention, testing, and treatment for transgender people.

I’m here in my professional capacity to discuss sustainability in the HIV response, but I would be remiss to not talk about what this means in real life.

I, myself, am a gay man and a transgender man. My birth certificate still records my sex as Female — I’ve not been able to have that changed – but I’m fortunate to have my German residency and my US passport more accurately acknowledge me as Male.

When accessing HIV testing as a trans man who has sex with men, I’ve often been made invisible when testers assume from my appearance that I am a non-transgender male and record my test results accordingly. When I have then come out as trans, because I know how important data collection is for trans people (even though coming out can feel scary sometimes), I have been informed I have no HIV risk as a trans man (which I guarantee you is very inaccurate) and received no HIV counseling.

In recent years, I’ve been fortunate to have access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP), but not everyone is so lucky. One of my oldest friends is also a trans, gay man. He requested PReP from his large healthcare provider while he was in a sero-discordant relationship with a man who was HIV positive. My friend, though, was denied a prescription – explicitly because he was a transgender man. A month later, my dear friend tested positive for HIV.

Recently I was talking with a group of trans men from at least 10 different countries. All shared that they actively had sex with men, yet none of them had ever taken an HIV test because they were afraid of stigma in their home countries and healthcare systems.

We can do better. We MUST do better.

Recommendations

I want to end with some recommendations for sustaining our progress thus far.

First, we must build urgency and buy-in for resourcing the global AIDS response. We know HOW to end the epidemic, but we need the political will and financial resources to do so. Leadership from UNAIDS and Member States will continue to be critical in steering the field towards a successful and inclusive response to the HIV and AIDS epidemic.

Second, we need to think and fund intersectionally. In this shifting landscape, we need to engage human rights and healthcare funders and help them recognize their pivotal role in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Simultaneously, it’s crucial for HIV donors to understand that without investments in human rights and health care for key populations, including trans individuals, we will not fully eradicate the epidemic. We can’t separate community health from the human rights of key populations.

Third, we need to collectively increase the proportion of funding for advocacy and support key populations to create enabling environments. Civil society must be better resourced to counter socio-political barriers and criminalization that too-often creates an environment of fear and mistrust, undermining efforts to address the HIV epidemic.

Finally, we need to reduce barriers to supporting key population groups most impacted by HIV and AIDS. To this end, we should ensure funds reach as close to the affected individuals as possible by funding community organizations with expertise working with key populations. This may involve partnering with larger intermediaries or key population networks, when necessary, but prioritize those with established relationships and credibility in the communities they serve. Explore opportunities to give to and through intermediary and community-rooted funders, such as the International Trans Fund or the Red Umbrella Fund, while also working supportively with them to help build their capacities and scale their efforts. And, as much as possible, offer long-term, flexible, and unrestricted funding to address both immediate needs and long-term planning.

In closing, I urge you to act in your official capacities to help fill the funding gaps facing the global HIV response, and to commit to more equitably addressing the needs of key populations. I truly belief we can bring an end to the AIDS epidemic in our lifetimes, but we’ll never do so while we criminalize or marginalize those most at risk for HIV.

Key populations urgently need your leadership and commitment.

Trans people urgently need your leadership and commitment.

No matter where you’re from, or your political orientation, our lives, our futures, and an end to HIV depends on you.